Building NVSHMEM from Scratch: GPU-Initiated Networking#

Abstract#

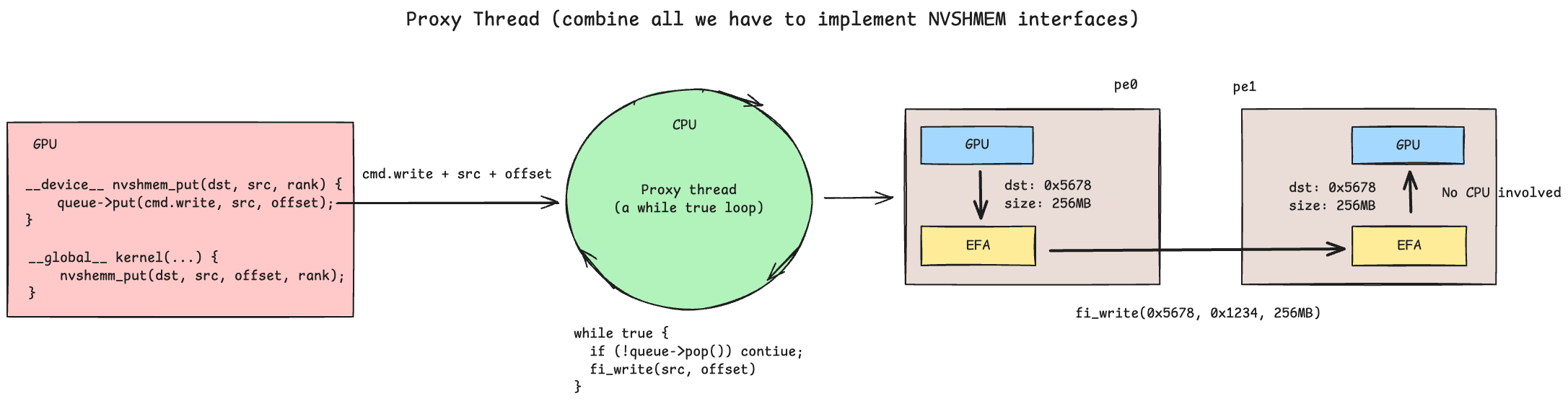

GPU-to-GPU communication is critical for large language model (LLM) training and inference, as modern models cannot fit on a single GPU or even a single node. This necessitates partitioning model parameters across GPUs and using collective communication to aggregate results. NCCL is a widely-used collective library that achieves high throughput over RDMA fabrics such as InfiniBand and AWS Elastic Fabric Adapter (EFA). Recently, GPU-Initiated Networking (GIN) [3] has gained attention for its ability to fuse CUDA kernels with GPUDirect communication, reducing kernel launch overhead and improving overlap. DeepEP [6] exemplifies this approach—a high-performance Mixture-of-Experts (MoE) layer dispatch/combine implementation that significantly reduces All-to-All collective latency using NVSHMEM with InfiniBand GPUDirect Async (IBGDA). However, not all RDMA providers support IBGDA (at least as of late 2025). Instead, they rely on a “Proxy Thread” technique to achieve GIN. InfiniBand Reliable Connection (IBRC) uses this approach, as do similar implementations like UCCL [4] and MSCCL++ [5]. In this article, we present a systematic breakdown of how proxy thread solutions achieve GPU-initiated behavior over AWS EFA, and describe the design and implementation of a minimal NVSHMEM-like library.

Note

All source code and benchmarks are available at Libefaxx.

Introduction#

The rapid scaling of LLMs has made efficient GPU-to-GPU communication a first-class concern in distributed systems. Libraries such as NCCL [2] abstract collective operations over RDMA fabrics, but emerging workloads— particularly MoE architectures—demand finer-grained, kernel-level control over communication. NVSHMEM provides a GPU-initiated programming model where CUDA kernels directly issue put/get operations, enabling overlap of computation and communication without returning control to the host.

This article targets practitioners who wish to understand the internals of NVSHMEM/OpenSHMEM by building one from scratch. We decompose the problem into the following components and describe each in detail.

First, we discuss the RDMA transport layer, where we use libfabric [1] to initialize fabric objects, create endpoints, and manage completion queues over AWS EFA. We then examine hardware topology discovery using hwloc, which enables NUMA-aware placement by mapping GPU-NIC affinity through the PCIe hierarchy — a critical step for minimizing cross-switch latency on multi-NIC instances. Next, we describe the bootstrap phase, in which peers exchange endpoint addresses and memory region keys through an out-of-band channel (e.g., MPI or TCP) before any RDMA data transfer can occur.

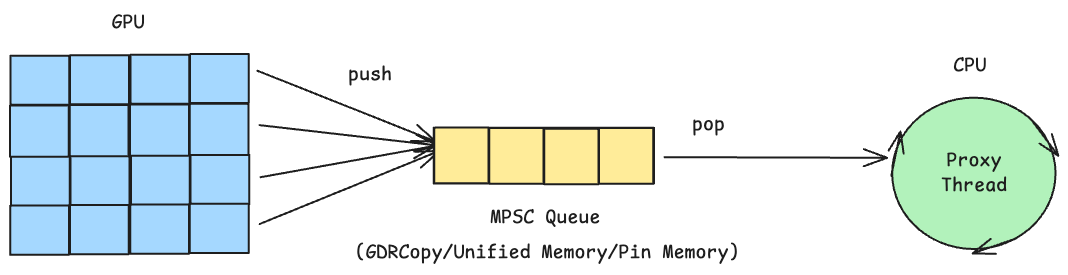

With the transport established, we cover two communication patterns supported by libfabric: two-sided SEND/RECV, which requires active participation from both peers, and one-sided RDMA WRITE, which allows a sender to write directly into remote registered memory without receiver involvement — the natural fit for NVSHMEM’s put/get semantics. We then present the GPU-CPU queue, a multi-producer single-consumer (MPSC) structure that enables GPU kernels to enqueue RDMA requests to a proxy thread — a CPU-side thread that dequeues and issues fabric operations on behalf of the GPU, bridging the gap when hardware does not support IBGDA.

Finally, we describe three remaining components that complete the design: symmetric memory, which provides a globally addressable memory space across all GPUs; GPUDirect RDMA via DMA-BUF, which enables zero-copy registration of GPU memory for direct NIC access; and CUDA IPC, which provides low-latency intra-node GPU-to-GPU data transfer through shared memory handles.

Fabric: RDMA Transport with libfabric and AWS EFA#

To perform RDMA operations, applications typically use low-level libraries such

as libibverbs (for

InfiniBand/RoCE) or libfabric (a

higher-level, provider-agnostic fabric interface). Since this article targets AWS

Elastic Fabric Adapter (EFA), we use libfabric — the recommended interface

for EFA. The AWS EFA provider in libfabric handles the

Scalable Reliable Datagram (SRD)

protocol internally, so applications do not need to manage reliability or

ordering at the transport layer.

libfabric Object Hierarchy#

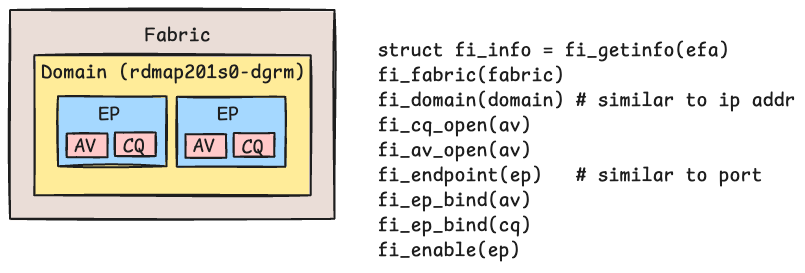

The diagram below illustrates the core libfabric object hierarchy used to set up RDMA communication over EFA:

Fabric — represents the physical network (e.g., an EFA device).

Domain — maps to a specific network interface, analogous to binding to an IP address. Each domain provides access to resources such as memory registration and address resolution.

Endpoint — a communication channel, analogous to a socket. Each endpoint is associated with:

An Address Vector (AV) — a table that maps peer addresses for connectionless (datagram) communication.

A Completion Queue (CQ) — used to poll for RDMA operation completions (e.g., send/recv/write done).

The full initialization sequence can be found in efa.h.

Querying EFA Devices with fi_info#

On AWS EC2 instances with EFA enabled (e.g., p4d.24xlarge,

p5.48xlarge), available fabric providers can be queried using the

fi_info utility:

$ fi_info -p efa

provider: efa

fabric: efa

domain: rdmap201s0-dgrm

version: 203.10

type: FI_EP_DGRAM

protocol: FI_PROTO_EFA

The output shows that the EFA provider exposes a datagram endpoint

(FI_EP_DGRAM) using the FI_PROTO_EFA protocol. The domain field

identifies the specific EFA device. On multi-NIC instances (e.g.,

p5.48xlarge with 32 EFA interfaces), fi_info lists multiple

domains — one per NIC — which is important for topology-aware placement

discussed in the next section.

Topology: GPU-NIC Affinity and NUMA-Aware Placement#

Hardware topology awareness is essential for achieving optimal RDMA performance

in multi-GPU systems. On instances like AWS p5.48xlarge, each GPU is

physically closer to certain EFA NICs and CPU cores through the PCIe topology.

Routing RDMA traffic through a topology-local NIC avoids costly cross-NUMA or

cross-PCIe-switch transfers.

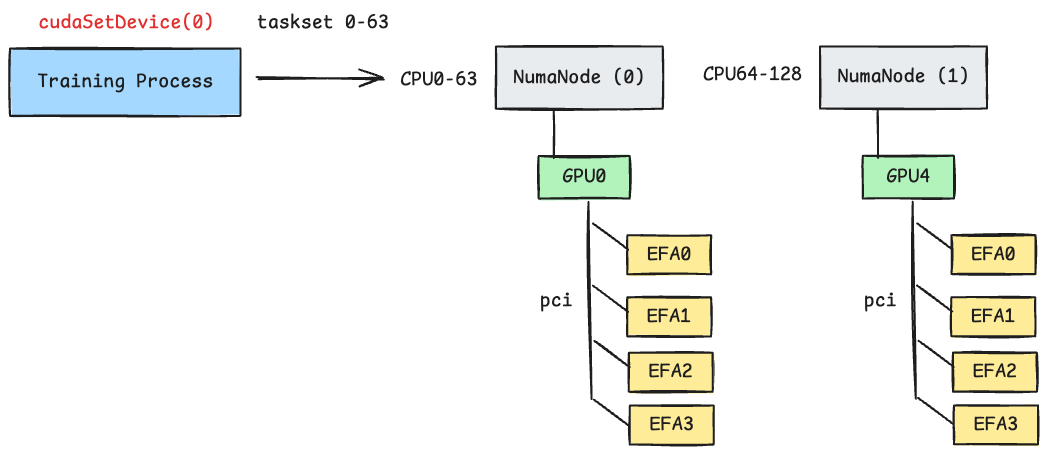

The diagram below illustrates this principle. If a process is bound to GPU 0, routing RDMA traffic through the EFA device on the same PCIe switch minimizes latency. Using a distant NIC (e.g., one closer to GPU 4) forces data to traverse additional PCIe hops, increasing transfer time.

Detecting Topology with hwloc#

One approach to discovering hardware topology is to parse

/sys/bus/pci/devices directly, but this is error-prone and difficult to

maintain. A more robust approach is to use

hwloc — a portable library for

querying the hierarchical topology of CPUs, caches, NUMA nodes, and PCI

devices. The programming pattern resembles a depth-first search (DFS) pre-order

traversal over a tree data structure. Basic usage examples are available in the

hwloc cheat sheet. For a real-world example of

detecting GPU-NIC affinity on AWS p5.48xlarge and using taskset to pin

processes to topology-local CPU cores, see

affinity.h.

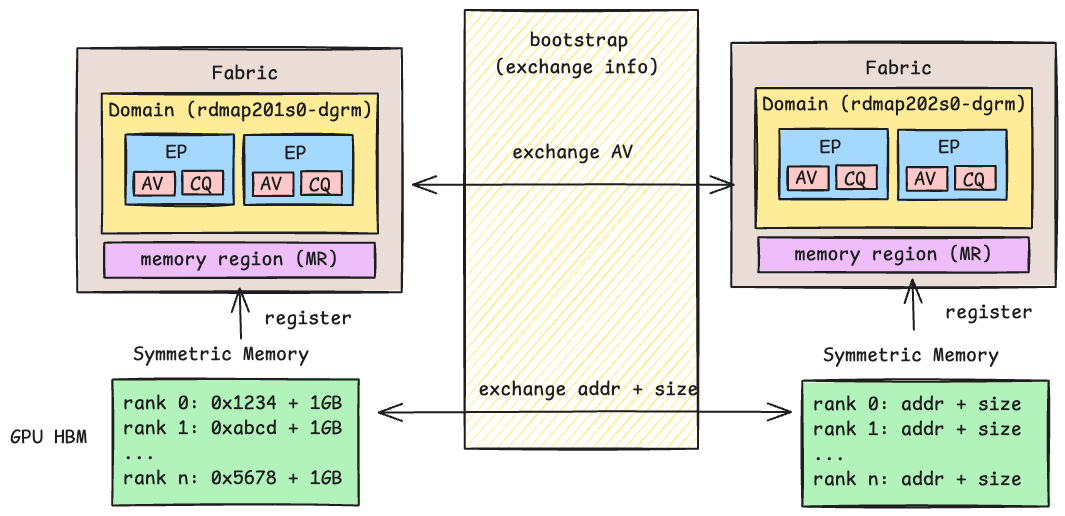

Bootstrap: Out-of-Band Connection Setup#

Unlike traditional networking stacks where protocols like ARP handle address discovery automatically, RDMA requires an explicit out-of-band (OOB) exchange to set up connections. Before any RDMA data transfer can occur, peers must exchange endpoint addresses and memory region keys through a separate control channel — a process known as bootstrapping.

Common bootstrap methods in the RDMA ecosystem include:

MPI — NCCL and NVSHMEM can use MPI collectives (e.g.,

MPI_Allgather) to distribute connection identifiers such asnccl_idacross all ranks.TCPStore — PyTorch’s distributed runtime uses TCPStore as a key-value store to exchange connection information (e.g., rank addresses, NCCL IDs) between processes.

Once the RDMA connection is established and memory regions are registered, the

OOB channel is no longer needed for data transfer. In our implementation, the

symmetric memory layer uses MPI_Allgather to exchange remote RDMA addresses

and memory region sizes. Further details are available in

fabric.h.

Communication: RDMA Verbs and Data Transfer Patterns#

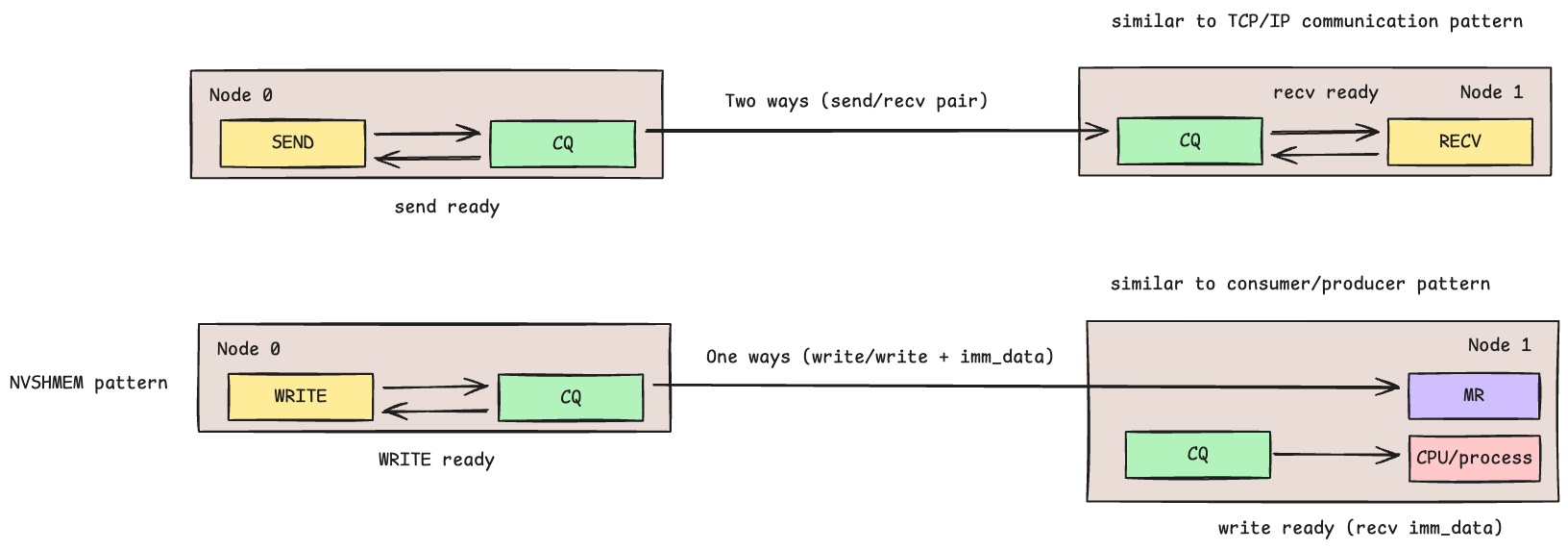

libfabric supports two primary communication patterns, each suited to different use cases.

Two-Sided Communication (SEND/RECV)#

This pattern resembles traditional TCP/IP socket communication. Both the sender

and receiver must actively participate — the sender calls fi_sendmsg and

the receiver calls fi_recvmsg. Each side’s completion queue (CQ) signals

when its respective operation completes. This is useful when the receiver needs

to know exactly when data arrives and control where it lands.

One-Sided Communication (RDMA WRITE)#

This pattern resembles a producer-consumer model with shared memory. The writer

uses fi_writemsg to write directly into the remote node’s registered memory

region (MR) — the remote CPU is not involved in the data path. Only the

writer’s CQ signals completion; the remote side has no automatic notification

that data arrived.

To notify the remote side, RDMA provides write with immediate data

(FI_REMOTE_CQ_DATA). The writer attaches a small immediate value to the

write operation. When the write completes, the remote CQ receives a completion

event containing this immediate data, signaling that new data is available.

This is commonly used as an “end-of-write” tag.

Implementation examples for both patterns are available in Libefaxx: Send/Recv benchmark and Write benchmark.

Why NVSHMEM Uses One-Sided Semantics#

The name “NVSHMEM” (and OpenSHMEM) might suggest it is merely a shared memory

IPC library. However, NVSHMEM also supports inter-node communication over RDMA.

The “SHMEM” terminology reflects the programming model: like shared memory IPC,

the communication is one-sided — a producer writes to a remote address without

the consumer explicitly receiving. RDMA one-sided write maps naturally to this

model: the caller specifies a remote virtual address and offset, and the NIC

performs a DMA transfer directly into remote memory. This is why one-sided RDMA

is the foundation for NVSHMEM’s nvshmem_put / nvshmem_get APIs.

GPU-CPU Queue: Low-Latency Signaling for Proxy Threads#

The proxy thread architecture relies on a GPU-CPU queue to coordinate between GPU kernels and the CPU thread that issues RDMA operations. Since GPU kernels run thousands of threads, this is typically implemented as a multi-producer, single-consumer (MPSC) queue — many GPU threads enqueue requests, while a single CPU proxy thread dequeues and processes them.

Several memory strategies can implement this queue, each with different trade-offs:

GDRCopy — Maps GPU memory to CPU address space via PCIe BAR (Base Address Register). The CPU can directly read/write GPU memory without invoking CUDA APIs.

CUDA Unified Memory — Automatically migrates pages between GPU and CPU on access. Simpler to program but incurs page fault overhead on first access.

Pinned (Page-Locked) Host Memory — CPU memory allocated with

cudaHostAllocthat GPUs can access directly via PCIe.

For benchmarks comparing these approaches, see the Command Queue Implementation Comparison in Libefaxx.

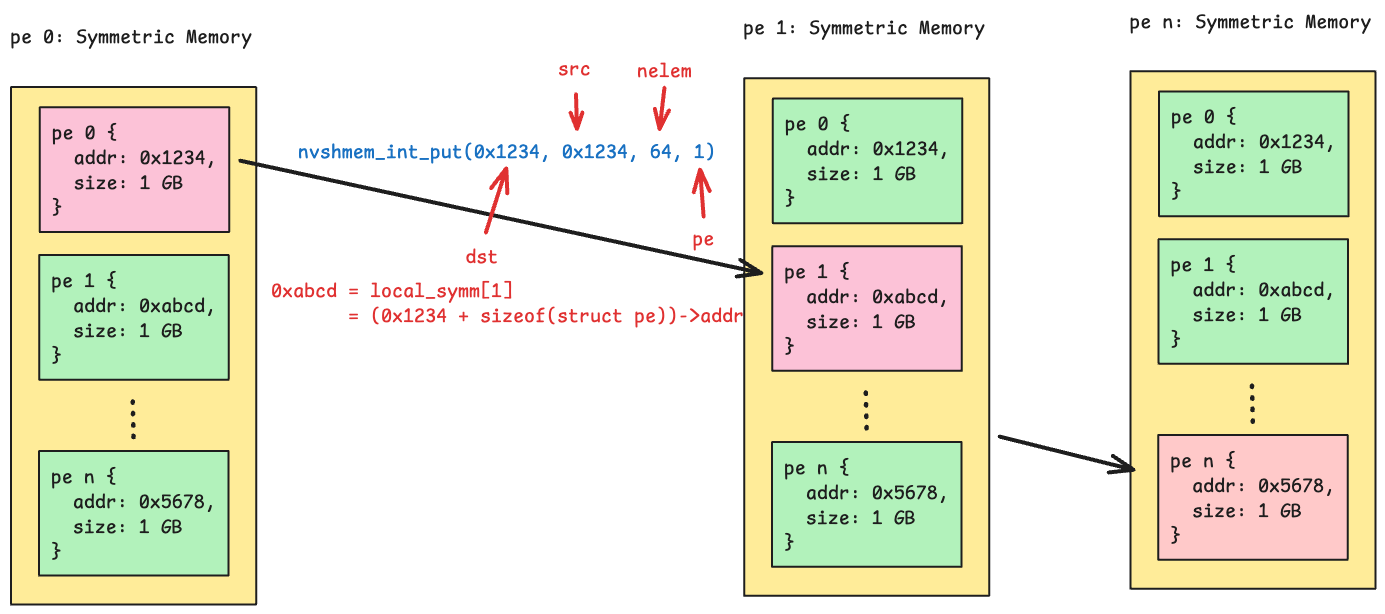

Symmetric Memory#

In NVSHMEM’s Memory Model, symmetric memory refers to allocations that have the same name, type, and size on all PEs (Processing Elements). This uniformity is required because each PE must maintain RDMA metadata — remote virtual addresses and memory region sizes — for every other PE, so that one-sided operations can directly access remote memory without coordination.

The diagram below illustrates a straightforward implementation of the symmetric

memory data structure. Each PE’s local symmetric object holds both a block of

its own allocated memory and the remote virtual addresses of all other PEs.

When a shmem-like API such as nvshmem_int_put is called, the library

looks up the target PE’s remote address and issues an RDMA write directly into

that region.

For implementation details, see memory.h in Libefaxx.

GPUDirect RDMA#

Standard RDMA requires data to reside in registered host memory. When the source data lives on a GPU, a naive approach copies GPU memory to a pinned host buffer, registers it, and then issues the RDMA operation — adding a full device-to-host transfer to every communication. GPUDirect RDMA eliminates this copy by allowing the NIC to read from and write to GPU memory directly over PCIe, without staging through host memory.

DMA-BUF: Exporting GPU Memory to the NIC#

The Linux kernel’s DMA-BUF framework provides a standard mechanism for sharing memory buffers between devices. For GPUDirect RDMA, the workflow is:

Allocate GPU memory with

cudaMalloc.Export a DMA-BUF file descriptor using

cuMemGetHandleForAddressRangewithCU_MEM_RANGE_HANDLE_TYPE_DMA_BUF_FD.Register the memory with libfabric using

fi_mr_regattrwithFI_HMEM_CUDAand the DMA-BUF descriptor infi_mr_dmabuf.

Once registered, the NIC can perform RDMA read/write operations directly against GPU memory through GPU virtual address. The DMA-BUF file descriptor is closed after registration, and the memory region is deregistered when no longer needed.

For the full implementation, see buffer.h in Libefaxx.

CUDA IPC#

RDMA handles inter-node communication, but GPUs within the same node are connected by NVLink — a high-bandwidth interconnect that provides up to 3600 Gbps on H100 GPUs, far exceeding what any network fabric can offer. CUDA IPC (Inter-Process Communication) allows processes to share GPU memory across process boundaries, enabling direct GPU-to-GPU transfers over NVLink without involving the CPU or NIC.

IPC Handle Exchange#

The setup follows a pattern similar to RDMA bootstrapping:

Each rank calls

cudaIpcGetMemHandleto export a handle for its GPU buffer.Handles are exchanged across local ranks via

MPI_Allgather(or any OOB channel).Each rank calls

cudaIpcOpenMemHandleon peer handles to obtain a device pointer that maps into the remote GPU’s memory.

Once opened, a GPU kernel can write directly to a peer GPU’s buffer using the

mapped pointer — the transfer occurs over NVLink with no CPU involvement. A

__threadfence_system() ensures writes are visible to the remote GPU. This

access pattern — writing to a remote address without receiver participation —

is identical to RDMA one-sided semantics, which makes CUDA IPC a natural fit

for the symmetric memory abstraction.

Integration with Symmetric Memory#

Because CUDA IPC and RDMA one-sided write share the same put/get programming model — both operate on a remote virtual address without receiver participation — the symmetric memory layer can store IPC pointers and RDMA remote addresses side by side in a single data structure. At runtime, the library checks whether the target PE resides on the same node. If so, it writes directly through the IPC pointer over NVLink; otherwise, it enqueues the request to the proxy thread for RDMA delivery. This routing is transparent to the caller, and the performance difference is substantial: NVLink IPC transfers can reach ~2971 Gbps (78% of H100 NVLink peak), as shown in the NVLink IPC benchmark.

For implementation details, see symmetric.h in Libefaxx.

Simple NVSHMEM Implementation#

With all the building blocks in place — RDMA transport, topology discovery,

bootstrap, proxy thread, symmetric memory, GPUDirect RDMA, and CUDA IPC — we

can assemble a minimal NVSHMEM-like API. The goal is to provide familiar

shmem_* functions that CUDA kernels call directly, while the library

transparently handles intra-node vs. inter-node routing underneath.

API Surface#

The host-side API mirrors NVSHMEM’s structure:

shmem_init/shmem_finalize— bootstrap MPI, discover topology, create EFA endpoints, and establish connections.shmem_malloc/shmem_free— allocate symmetric memory with DMA-BUF registration, exchange RDMA keys viaMPI_Sendrecv, and exchange CUDA IPC handles among local ranks.shmem_my_pe/shmem_n_pes— query the current PE index and total PE count.shmem_barrier_all— global barrier across all PEs.

On the device side, shmem_int_p (and other typed variants) perform a

one-sided put from within a CUDA kernel. The implementation checks the target

PE’s IPC pointer: if non-null (same node), it writes directly over NVLink;

otherwise, it writes to local symmetric memory, issues a __threadfence_system,

and pushes a request to the proxy thread’s MPSC queue for RDMA delivery. The

blocking variant calls shmem_quiet to wait until the proxy thread confirms

completion.

Example#

The following example demonstrates a simple ring shift — each PE writes its rank to the next PE’s symmetric buffer, equivalent to the NVSHMEM example:

#include <shmem/shmem.cuh>

template <typename Ctx>

__global__ void simple_shift(Ctx ctx, int* target, int mype, int npes) {

int peer = (mype + 1) % npes;

shmem_int_p(ctx, target, mype, peer);

}

int main() {

shmem_init();

int mype = shmem_my_pe();

int npes = shmem_n_pes();

int* target = static_cast<int*>(shmem_malloc(sizeof(int)));

auto ctx = shmem_ctx(target);

simple_shift<<<1, 1>>>(ctx, target, mype, npes);

// ... run proxy thread for inter-node RDMA if needed ...

shmem_barrier_all();

shmem_free(target);

shmem_finalize();

}

For the full API implementation, see shmem.cuh. For the complete working example including proxy thread setup, see the shmem experiment in Libefaxx.

Conclusion#

The goal of this article was to learn how NVSHMEM-like libraries work by building one from scratch. Recent Mixture-of-Experts (MoE) implementations such as DeepEP have shown that high-performance GPU-initiated communication can significantly improve dispatch/combine latency beyond what naive All-to-All collectives achieve. To better understand the technologies behind these projects, I conducted a series of small experiments covering RDMA transport with libfabric, NUMA-aware topology discovery, out-of-band bootstrapping, one-sided communication, MPSC queues for proxy threads, symmetric memory, GPUDirect RDMA via DMA-BUF, and CUDA IPC over NVLink.

I am grateful to the open-source projects referenced throughout this article — NVSHMEM, UCCL, MSCCL++, and DeepEP — whose designs and source code were invaluable in deepening my understanding of RDMA and CUDA communication. This article represents my current understanding, and I welcome any corrections or suggestions. For additional experiments and benchmark results, please refer to the Libefaxx experiments.